India’s Digital Personal Data Protection (DPDP) Act, 2023 introduces consent as the core legal basis for processing personal data. In doing so, it moves away from implicit and bundled permissions towards an architecture built on user agency, traceability, and auditability. This is a significant shift. Unlike global regulatory approaches that treat consent as a one-time formality, the DPDP framework positions it as an ongoing, verifiable transaction that must be transparent, revocable, and purpose-bound. In principle, this is a step in the right direction. A system that embeds consent management into its design – rather than layering it on as an afterthought – sets the stage for genuine data governance in India’s expanding digital economy.

The law outlines the concept clearly. Section 6 of the DPDP Act defines what valid consent must look like – free, specific, informed, unconditional, and unambiguous, provided through clear affirmative action. It also introduces the concept of “Consent Managers” as registered intermediaries who facilitate consent between users (data principals) and data fiduciaries. The Draft Rules released in January 2025 expand on this by defining roles, responsibilities, and qualifying criteria for Consent Managers – such as neutrality, financial fitness, and technical capacity. Finally, in June 2025, the government released the Consent Management Architecture Business Requirement Document (BRD), which lays out the technology building blocks needed to implement this framework in practice. The progression is logical: the Act defines the principle, the Rules add procedural scaffolding, and the BRD translates these into technical modules and workflows.

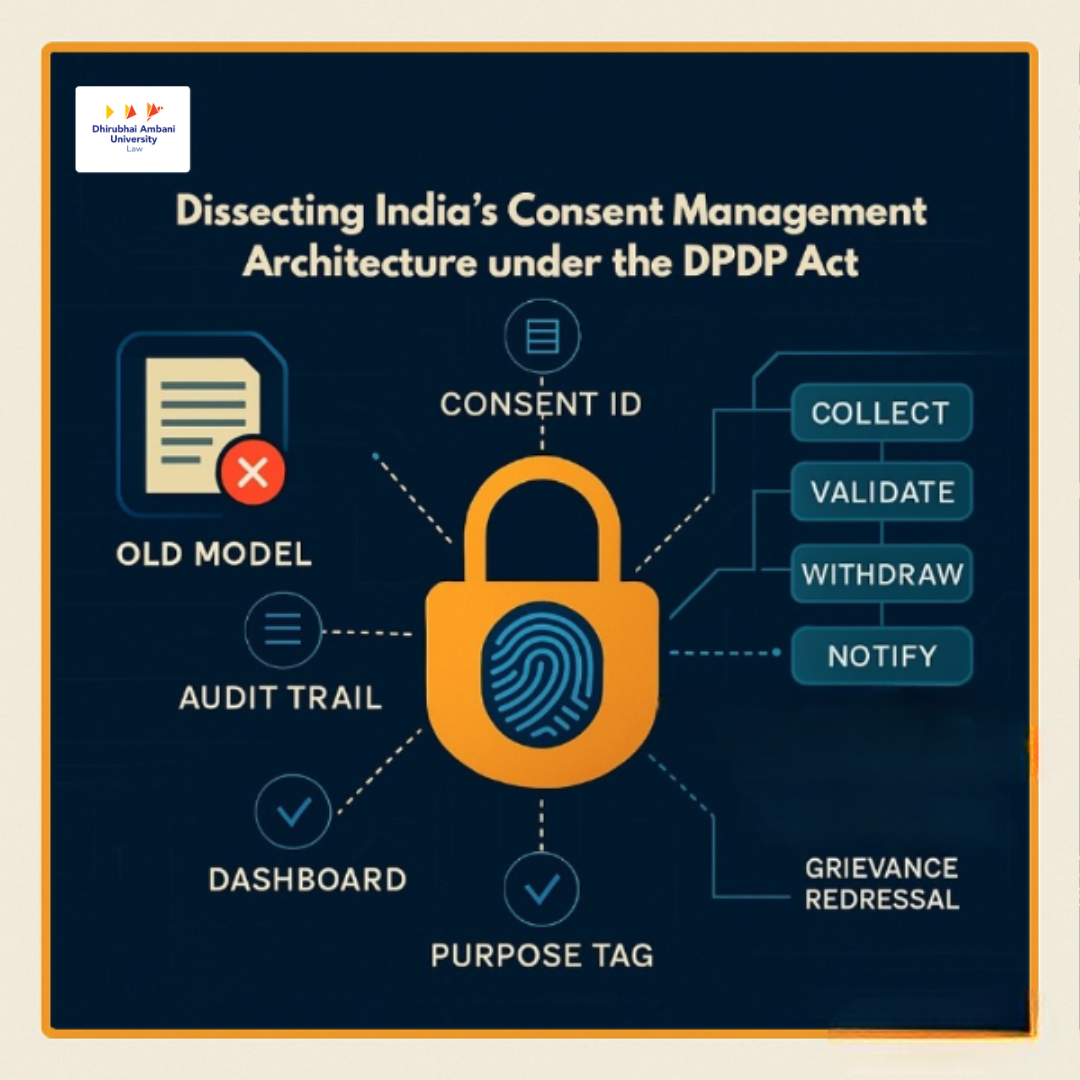

The consent architecture in the BRD is organized into modules – collection, validation, withdrawal, dashboards, notifications, audit trails, and grievance handling – each mapped to a specific legal requirement. The design is API-driven and modular, intended to be interoperable across platforms and sectors. However, while the direction is sound, the actual implementation raises certain operational issues. Three challenges merit particular attention: verifiability of consent, enforceability of withdrawal and purpose limitation, and effectiveness of user control.

First, the law requires that consent be not only given through affirmative action but also stored in a manner that allows it to be proven, reviewed, and audited. This means consent becomes an artefact with metadata, timestamps, and purpose tags. The BRD addresses this with a Consent Collection module that mandates structured formats, unique consent IDs, and event logs. These technical elements support traceability. But what’s missing is standardization of how purposes are defined and tagged. Without a shared taxonomy of purposes across sectors, different platforms may describe similar data uses in inconsistent ways, making validation by Consent Managers difficult. A purpose registry or standard-purpose ontology is needed to ensure consistency and allow for machine-readable validation across ecosystems.

Second, the DPDP framework gives data principals the right to withdraw consent at any time, and mandates that data collected for one purpose not be reused for another without renewed consent. The BRD reflects this by including modules for withdrawal, downstream notification, and consent status APIs. It also recommends event-driven workflows that allow a user’s revocation of consent to propagate through data fiduciaries and processors. However, the BRD is unclear on how enforcement of deletion or stoppage of use is verified. If a user withdraws consent for data used in profiling or analytics, does the system ensure derived insights are also purged or deactivated? This raises technical and regulatory questions that the BRD defers. The actual enforcement of purpose limitation will require additional compliance checks, retention policy flags, and possibly random audits by the regulator or certification authorities.

Third, the promise of the consent architecture rests on user visibility and control. The Act gives data principals the right to access and manage their consent status. The BRD introduces a Consent Dashboard module that aims to provide a unified, multilingual interface for users to view, update, and revoke consents. This interface is critical for trust-building. However, the assumption that all data fiduciaries and processors are API-ready is optimistic. In low-tech sectors like small retail, offline lending, or healthcare, the real-time integration envisioned by the BRD may not materialize easily. Furthermore, the dashboard lacks deeper grievance functionality. While ticketing and logs are mentioned, there are no binding Service Level Agreements or escalation pathways outlined. For a system meant to empower users, the grievance workflow is under-specified.

The Account Aggregator (AA) model in India offers useful lessons for improving the Consent Management architecture under the DPDP framework. The AA system – operational in the financial sector – successfully demonstrates how consent can be modular, cryptographically secure, and traceable without retaining personal data. It achieves interoperability through standardized consent artefacts, sector-specific taxonomies, and regulatory supervision. The Consent Management framework under the DPDP Act can borrow from AA’s structured data schemas, pre-approved purpose definitions, and consent lifecycle enforcement through event logs. Moreover, the regulatory clarity provided by the Reserve Bank of India in the AA ecosystem, including clear onboarding criteria and compliance audits, could serve as a template for the Data Protection Board of India (DPBI), under Section 18 of the DPDP Act, to operationalize Consent Manager registration, certification, and monitoring more rigorously. These lessons are essential for avoiding fragmentation and ensuring consistent user experience across sectors.

In conclusion, the Consent Management Architecture under the DPDP framework is conceptually strong and reflects lessons from earlier data ecosystems like the Account Aggregator model. The Act, Draft Rules, and BRD align well in terms of direction, with a clear flow from legal requirement to system design. But moving from design to enforcement will require standardization (of purpose tags), oversight (of consent withdrawal propagation), and support infrastructure (for low-tech fiduciaries and grievance handling). The next phase of development should focus on these implementation gaps, possibly through sandbox pilots, sector-specific templates, and a clear roadmap for Consent Manager accreditation and supervision. These operational processes will facilitate the consent framework to deliver on its promise of data protection through meaningful user control.